Chapter: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Maps

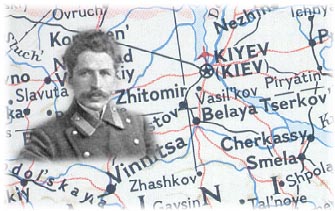

Kiev area, 1981 (National Geographic)

A Russian Chronicle

The Tale of Michael L. Zlatovsky

Chapter 1

I was born in the year 1881 in the south of Russia, the Ukraine, in a small town called Pereyaslav, better known to Yiddish-speaking people by the somewhat derogatory name of Kasrilovka. This name was given to the town by its native son, the great Jewish humorist Rabinovitz, generally known under the pen name of Sholom Aleichem.

Since the small towns of the Pale differ very little from each other, Kasrilovka symbolizes any poor and stagnant town, together with all its institutions–religious, educational, and charitable. Likewise, a Kasrilak–any inhabitant of such a town as pictured in the writings of Sholom Aleichem–typifies the average ghetto Jew with his mode of living, his struggle for existence, his innate sense of humor, his sorrows and joys. However, while Pereyaslav is the typical small town, it has one distinction–its antiquity. The name appears in the history books as far back as the 9th century, antedating even Kiev, “Mother of Russian Towns.” There on the fortified banks of the Trubez River fierce battles were fought between the Russians, then still idolaters, and the various invaders. Chief among them were the Khazars who, in the 8th century, embraced Judaism and, moving from the Black Sea to the Caspian, established themselves along the Volga River, repeatedly invading Russia with varying degrees of success.

When the Grand Duke Vladimir, “The Saint,” decided to abandon paganism, the Khazars sent their emissaries, along with the Christians and Mohammedans. According to legend, Vladimir rejected Mohammedanism because it forbade drinking, saying that “drinking is the joy of the Russian people,” and he reputedly gave the cold shoulder to the Khazars because the Jews were a scattered nation and he did not want to share a like fate. Most likely, he declined their offer because the power of the Khazars was at that time declining. Soon afterward, they became extinct after having been defeated by the combined forces of the Russians and the Byzantines.

Pereyaslav appears again in the history of the 17th century because of the bloody events that took place in the Ukraine generally and in this town particularly. At that time, the Ukraine was under the domination of Poland, with the exception of the region situated at the lower part of the Dnieper River, the Zaporohie, or “beyond the water falls.” There the Cossacks established a military camp where peaceful occupations were shunned and drinking, fighting, and military exploits were extolled and practiced.

The great Russian writer, Gogol, in his novel, “Taras Bulba,” idealized the Cossacks as lovers of freedom, defenders of faith, and avengers of oppression by the Jews. However, the fact is that the camp was a semi-barbarous republic with a great admixture of Mongols, constantly engaged in war with the Turks, Tartars, and Poles, with the aim of pillage, torture, and rape.

In 1648, the leader of the Cossacks (called a Hetman, from the German Hauptmann) was a daring, cruel, and conspiring man–Bogodan Khmelnitski by name. He made peace with the Tartars and their combined hordes, moved into the Ukraine, and massacred the Jews with a ferocity far exceeding that of the Crusaders. Pereyaslav, where the invaders met with some resistance, was left in ruins. Its population was exterminated with the exception of a few “lucky” ones who were taken into slavery by the Tartars and eventually ransomed.

In the center of the Jewish district, there was at the time of my childhood a landmark that a popular legend connected with the massacres of 1648. It was an ancient church called “The Empty One.” According to legend, a beautiful synagogue once stood on this site. Desecrated and burned by the Cossacks, it was replaced by the “Empty” church. A Rabbi saint, so goes the story, put a curse on it. Since that time, the church had been sinking slowly into the ground so that only the cross remained visible from among the ruins. During the pogroms of the eighties of the last century, rumors were current that imported killers were hiding in the ruins, sharpening their knives in expectation of an order from those in power to exterminate the Jews. At all times, the church was supposed to be the abode of devils. Many an ignorant mother used this belief as a means of silencing a crying child or subduing a disobedient one. The result was that we children never dared pass the “Empty One” singly at night, while in the daytime when devils were powerless, we would linger about the premises never failing to spit three times and to pronounce a curse.

Because the lower part of the town along the Trubez River was once fortified, it became known as the “Fortress.” There lived the bulk of the Jewish population comprised of small traders, artisans, men engaged in religious and educational activities, honored but poorly paid, and men without any visible means of livelihood called “Luftmenschen” or men living on air. It was from this class of people, connected in one way or another with the grain and lumber export business, that occasionally one would strike it rich and move away from the Fortress. But, as a rule, one born there was destined to remain in the Fortress for life unless he emigrated to the “Golden Land,” as America was called in the ghetto.

At the age of four, I had the good fortune of escaping from the Fortress temporarily, having been adopted by my grandfather who lived in a village close to town. The years 1861 to 1881 under Alexander II were known as the liberal epoch and the Tsar as the Liberator because he freed the peasants from servitude. He also liberated the Jews who, under the despotic regime of his tyrannical predecessor, Nicholas I, had been oppressed and had suffered from various disabilities, chief among them juvenile conscription. Boys from the age of seven were torn from their homes and sent to central Russia where they were distributed among the peasants as serfs. At 21 they were taken into military service of 25 years' duration, providing they did not perish long before from cruel treatment and malnutrition. The first act of Tsar Alexander upon ascending the throne was to abolish this system of conscription.

Because of the benign attitude of the administration toward the Jews, amicable relations were created between the Jews and the Russians. Although Grandfather was the only Jew in the village, he experienced no difficulties, and his relations with peasants were most pleasant. His next-door neighbor, Pisarenko, often came to the house to smoke a pipe with Grandfather or to have a drink in company with other people of the village on Jewish or Christian holidays. On Fridays, Pisarenko invariably came to the house to taste the “gefillte fish.” After a few drinks, he would become mellow and effusive, trying to kiss Grandmother, to her great discomfort. His son, a boy of my age, was my playmate. In summer, we roamed the streets, flying kites, catching butterflies, and picking the abundant cherries and apples. In winter, we put up snowmen, skated on makeshift skates, and amused ourselves the best we could in the house when it was too cold to play outdoors.

Unfortunately, this idyllic life did not last long. The liberal regime was attacked from its inception from two different directions. The landowners who resented the loss of serfs, former functionaries of the despotic regime, the clergy, and the reactionary press all accused the liberals of “selling out” to the Jews to the detriment of the Russian people. On the other hand, the radicals demanded the establishment of a constitutional form of government, and the extremists–known at that time as nihilists–clamored for radical social reforms with the abdication of the Tsar and the formation of a republic. Under this double pressure, the regime became reactionary to a great extent. Since the Jews were always the scapegoats, their rights were abrogated, and their relations with the Russians degenerated.

Meanwhile, attempts were made to kill the Tsar, the most spectacular being the dynamiting of the Winter Palace–an attempt which was unsuccessful simply because the Tsar left the dining room where the dynamite had been placed just 10 minutes earlier than expected. Finally, on March 1, 1881, the Tsar was killed by five assassins, among them a Jewish woman named Heisa Helfund. This gave the reactionaries a chance to call it a Jewish plot and to put the blame for all disturbances on the Jewish people.

Pogroms broke out in a number of cities simultaneously in a particular pattern that tended to prove that they were preconceived and organized, rather than a spontaneous reaction of the populace. Unlike later pogroms, the rioters limited themselves to destruction and looting; but it was terrifying just the same, especially since rumors exaggerated and magnified the extent of the havoc. The reaction of the peasants in our remote village at first manifested itself with the substitution of the contemptuous “Zhyd” for the word Jew but with no other visible hostility. However, our turn was not long delayed.

I remember the event vividly. One beautiful summer day, I was sitting with Grandmother on the steps leading to the house when our good neighbor, Pisarenko, approached hurriedly and without uttering a word hit the window with a stick, shattering the glass. When I started to cry, Grandmother took me on her lap, saying, “Don't cry, my son, God is with us.” Meanwhile, Grandfather appeared on the scene. At the sight of him, Pisarenko threw away the stick and embraced him, muttering, “I love you, Velka, but this is the order of the Tsar.” The next morning Pisarenko took us to town in his wagon. While moving through the empty streets littered with broken glass and flying feathers, Pisarenko would brandish his stick at the sight of some hooligan and holler at the top of his voice, “These are my Zhyds! Don't you dare touch them!” All I remember of my arrival at the house was being lowered into a cellar along with some other children and women. Thus, I returned to the Fortress and to long years of misery and privation.

The liberal era had come to an end. The new Tsar, Alexander III, of whom it was said that he had the build of a rhinoceros and the brains of a chicken, surrounded himself with rabid Jew-baiters. Chief among them was his tutor, Pobedzonostsov, the “Grand Inquisitor.” Under his influence, the so-called Temporary Rules were promulgated. Jews were expelled from the villages and were forbidden to possess land. A school norm of 10 percent in the Pale and three percent in the restricted areas was introduced. All government and city functionaries were summarily dismissed. A special tax was imposed on Jewish merchants; industrialists were forbidden to hire Jews in any capacity. The clergy denounced them from the pulpits, and the press attacked them collectively and individually. Discouraging was the fact that none of the influential men of letters such as Tolstoy or Turgenev came to the defense of the Jews. The only one who dared do so was a provincial novelist, Korolenko by name. He published a sharp protest under the title, “I Accuse,” the same words later used independently by Zola in his defense of Dreyfus. Korolenko paid for his daring by confiscation of his pamphlet, which had no effect on the situation, and by imprisonment as well.

So drastic were the restrictive laws that Pobedzonostsov believed he had solved the Jewish problem. “One-third of the nation will starve to death,” he said, “one-third will embrace Christianity, and the rest will emigrate.” However, he underestimated the inner strength of the long-suffering, martyred, and crucified nation. As the great Russian poet, Pushkin, said, “A heavy hammer shatters glass and forges steel.” The Jews starved but did not die. Nor did they become baptized. The pogroms and the draconic measures following had the opposite effect of that expected by the instigators.

During the liberal era, there had been a strong tendency, largely among the intelligentsia, toward assimilation–so much so that during the pogroms bewildered children sometimes asked their fathers, “What is this? Are we also Jews?” Now a great many of those assimilated turned nationalist and came back to the fold of Judaism. Students at Kharkov University formed a group known as “Bilu,” which is a Hebrew abbreviation meaning, “To the House of Jacob we go,” and to Palestine they went. Thousands of high school graduates barred from the universities by the school norm went abroad to study instead of taking the easy path of apostasy. Cases were known where baptized Jews clandestinely practiced the Jewish rituals like the Marranos of old in Spain. One play presenting such a case was popular with the anti-Semites. It was called, “The Baptized Zhyd Woman,” and, while wholly fictitious, was apparently intended to prevent such an occurrence by emphasizing the dire consequences the woman suffered for abandoning the new faith.

Where the “Grand Inquisitor” was right was in his prediction of mass emigration. America became the goal, the “pium desideratum” of the ghetto Jews, giving rise to a mass exodus that gained momentum from year to year until stopped by restrictive emigration laws. Luckily, by that time our family was already firmly established in the United States, enjoying the blessings of freedom and security.