Chapter: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

A Russian Chronicle

The Tale of Michael L. Zlatovsky

Chapter 19

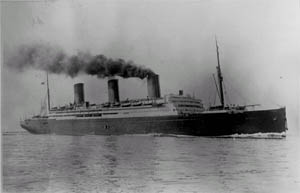

The Berengaria--our travel ship

In Russia, my sailing experience was limited to a few hundred miles on the Dnieper River. Because of competition between two steamship companies, it cost me 10 cents (!), and the accommodations were all it was worth. The passengers of first and second class had some advantages, having been given primitively arranged cabins. As compared with this steamer, the Berangharia looked to us like a swimming palace. We were given a cabin of our own with soft bunks and not much else. The food, served in a big hall, was good; and one day we were given a big dinner with fruits and wine--it was the 4th of July.

The first day of the voyage was stormy, and what with nausea and malaise we were dead to the world. Later the storm abated, the ocean was calm, and we spent all the day on the deck among a conglomeration of different nations, mostly Slavs. All in all, I was satisfied with the situation until I saw how the privileged ones fared. The supervisor of the steerage was an ex-sailor who visited Russia at different times and spoke a little Russian. With my limited English and his inadequate Russian we managed to keep up a conversation and exchanged views on both countries, Russia and the States. As a favor to me, he ordered the purser to take me around the ship. The guide, hardly expecting a tip, was ungracious; and, as we reached the first class, he accelerated his pace as if afraid that the fine ladies and the dignified gentlemen would be contaminated by the presence of a plebian. However, I could not fail to notice the beautiful knee-deep rugs, the rich furnishings, the tennis court, and above all the swimming pool--the first and the last indoor pool I saw in my life.

It was a revelation to see how the rich lived and were treated. The class distinction came more sharply in focus because of an experience one night. It was stuffy in the cabin, and we went on the deck. The woman doctor joined us. I was surprised that nobody was on the steerage deck while there was a crowd on the other part of it reserved for the “class” people. It was not long before I found the reason. A man approached and ordered us off, saying that steerage passengers were not allowed on the deck after sundown. The woman doctor was especially indignant. She was young, beautiful, and ambitious. Later we received a letter in which she stated that this little incident was a premonition of what could be expected in this country. She added that she did not get along with her relatives who considered her an ingrate and that she might go back to Europe--any country at all. The word ingrate struck home because this was also the attitude of my family, or part of it, in the initial stages before I became independent. The relations between a “benefactor” and the recipient of the benefits are hardly normal. The last we heard from her was that she had settled in Germany and, likely as not, she may have perished under Hitler's regime.

Upon arrival in New York, we were taken to Ellis Island, called by the immigrants Castle Garden. We were interrogated, inspected by a physician, and given a clean bill of health. The customs officials opened the box and being satisfied it contained books only, closed it and put another seal on it. The meager baggage was not searched. The immigrants who were met at the pier by relatives or friends were allowed to leave. We expected to be met by my brother-in-law, Julius, who lived in Philadelphia, but he was not in sight. We were taken along with a few forlorn Slavs to a big hall, which was the ticket office. Our papers were inspected, and we were told that we would have to leave immediately for Duluth for which we had a train ticket. This was a terrible blow to us. My wife had not seen her brother for 20 years and, going away as far as Duluth, would not have a chance to see him for a long time if not forever. We also badly needed a rest and a chance to orient ourselves in this country.

The minor official in charge was a young Jewish fellow. We implored him to let us go to the city or, failing this, to let us go to Philadelphia. He was adamant: we must go at once to Duluth. My wife was terribly depressed; the children began to cry. I was at a loss as to what was to be done. The train was due to leave in six hours, and he threatened to lock us up until that time. Luckily, Julius arrived after a couple hours of waiting. He spoke to the official and handed him, as he told me later, a five-dollar bill, and we were permitted to leave with him. Thus, I learned that a bribe, which was an integral part of nearly all transactions in Russia, is also effective in the States.

There was great excitement at the reunion, but the joy of it was dampened by the fact that Julius learned for the first time about the death of his parents, while Julius' wife, who came from the same town of Belaya Tserkov, found out that a great part of her family was wiped out by the “Greens.” We told them about our trials and tribulations in the old country; and Julius, in turn, told us about the hardships he went through in trying to establish himself in the States. He never made a success of it. At that time he operated some kind of a poor man's department store in partnership with his brother-in-law. The store was on the ground floor of an ancient building in the heart of a commercial district. His family of four lived upstairs in five rooms, one of which was rented. The elevated train passed by the windows and filled the house with noise and dust if a window was opened. The quarters were by no means conducive to rest or comfort, but the family was very cordial, and my little daughter found a playmate in one of the daughters about her age.

The day after my arrival I awoke in the morning to find a young man looking at me intently, smiling and laboring with his jaws in some peculiar way. (He was chewing gum--a habit entirely unknown in the old country.) My first thought was that he might be crazy, but this notion was quickly dispelled. He proved to be a cousin of mine, the son of my Uncle Berel Bulkin, a man of inventive mind and great dexterity whom I had always admired. Upon his death, his family had migrated to the States.

My cousin was a mildly prosperous man. He owned a house in a nice residential district and possessed a car. We went to his home and spent two pleasant days there. We exchanged reminiscences about my uncle and his many talents. Other members of the same family and friends formerly from Pereyaslov came to see us, eager to know all about conditions in Russia generally and of their native town particularly. They, in turn, talked about their own experiences in the Golden Land; and, what with drinks served and with plenty of delicious food, it was all very pleasant and comforting. In observing the house, I was surprised by one thing. It was a full size portrait of my host mounted on a tripod. Beneath was an inscription in golden letters: “To our beloved president.” “No,” remarked my cousin noticing my surprise. “I am not president of the United States--not yet. I was president for three years of the Pereyaslov Lodge.” I found out later that it is easy to become president--of a kind--in the States.

One day my cousin took us for a ride to show us the city. In passing a district I noticed that nearly all the houses apparently inhabited bore a sign, “For Sale.” “This district,” said my cousin who noticed my bafflement “was a gentile district. Jews began to move in, and the gentiles are moving away.” Farther on, we passed another section where the “For Sale” signs were as numerous. “This,” said my guide without waiting for a question, “was a Jewish district. Negroes came to live there, and the Jews are moving away.” Thus, I had another lesson in discrimination--this time not because of financial status but because of religious and racial differences. This did not tally with my conception of America where all were presumably free and equal.

We spent two weeks in Philadelphia and then went to our destination, Duluth. We were met at the train with pomp and enthusiasm. There was a big crowd. My father was dead and my mother was half paralyzed, but I had three sisters and two brothers, and they all were there with in-laws and a crop of nephews and nieces, most of them born in this country. Friends of the family were also present. I was escorted to the home of my oldest sister, Eva, in a cavalcade of cars. It was good to see the family from whom I had been separated for over 20 years and to breathe the fresh air of freedom, but it was also overwhelming and confusing.

For some time I was persona grata. We were feted extensively and alternately at the homes of brothers, sisters, and cousins. Relatives and friends of the family, along with perfect strangers, would come to find out about their relatives and about conditions in Russia. They wanted to know if cannibalism was actually practiced in new Russia and whether women were socialized--this seemed to be a burning question as I learned later--and so on. As a result, there appeared in the local papers my portrait with a long article about my experiences with some exaggerations and distortions--and this was reprinted in the Twin Cities newspapers. The publicity brought more people to the house and letters from different parts of the country. A man from Milwaukee, if I remember correctly, asked if I could by any chance give him information about his brother, a doctor in Leningrad. As a matter of fact, I knew him very well, both having worked in the same hospital; but I did not like to inform him that his brother died of typhoid fever before my very eyes just one year previously.

Some crank from St. Paul threatened to get even with me “when the day comes” for spreading lies about the Communist regime, signing the letter “Proletariat.” A woman came from Cloquet and asked me to go back with her to see her invalid husband. He was a Polish immigrant and had no faith in American doctors who could not help him. I went and found him suffering from an incurable disease known as the Parkinson syndrome. I could not do more than the local doctors did--give him a few encouraging words and some sedatives. They paid me handsomely and because he felt better or, most likely, wanted to believe that he felt better, this family became faithful patients of mine, and other people from Cloquet came to see me when I was in practice.

All this was fine, but when the short holiday was over, I had to face reality, and it looked very ugly. I was confronted with a multitude of problems, the solution of which, at least in part, depended on the good will and the help of the family. I simply had to drift along for the time being and see what others could do for me. First of all, I had to find a place to live. I came to the States penniless and naturally could not rent an apartment, which was unattainable anyway because of a housing shortage. Thus, we came to live with my youngest sister, Sarah.

Her husband was an intelligent, efficient businessman and, while he was financially comfortable, he was by no means wealthy. He owned a modest house large enough for his family of four, but there was hardly room for another family of the same size. We had to double up, and we felt it was an imposition on them.

My sister was gracious to us, but minor frictions between the women and especially the children were inevitable. My wife's pride suffered, and she was very unhappy and cried a great deal. Her position was the worst because my relatives were, after all, strangers to her, and they spoke mostly English which she did not understand. Friends of my hosts would come to the house and, although their English was defective, they insisted on talking English in preference to Yiddish, which they spoke fluently. It looked to her as though they were taking on airs of superiority. She felt humiliated and miserable.

The plan of bringing me to the States was greatly influenced by my mother who lived with my older sister, Eva. Mother suffered from severe arthritis accompanied by pain, and it was her hope that I might help to relieve her pain and perhaps even cure her. The ways of the doctors here were strange to her, and she did not understand the language. It seemed to her that I, being interested in her personally, would do better. I could not do more for her than the local doctors, and this was disappointing to her and more than annoying to me.

A minor irritation was the question of what name I should use in this country. My youngest brother, Harry, came to America at the age of 11. The cumbersome name of Zlatkovski was a nuisance to him, since neither the pupils nor the teachers in school could pronounce it, let alone spell it. He had the same trouble in college and was afraid the name would be a hindrance in his prospective profession of attorney. He changed his name to Davis. His example was followed by my nephews, sons of my older brother, Herschel.

At the time of my arrival, Harry was a struggling lawyer. He was a man of great integrity, an intellectual in the best meaning of the word. He was rather conservative and had social ambitions, participating in many civic affairs from which he gained prominence. It may have seemed to him somewhat odd to introduce to society a brother with the name of Zlatkovski, and he was very eager to have my name changed in the same way as his. However, I did not like the idea of changing my name at my age, and my wife was very strongly against it. So I sacrificed a “k” after the “t” and remained a Zlatovski. As a matter of fact, the retaining of my name was an advantage in my practice because it attracted the few Polish and Russian people who could explain their troubles to me freely. That my name was mispronounced and misspelled was no great calamity. I was addressed as “Doctor” anyway.

There was also the matter of schooling for the children. My son, aged 11, a very bright and capable youngster, did not have much difficulty. He was placed initially in the lowest grade, but he learned the language quickly and was promoted nearly every month to a higher grade until, by the end of the school year, he was ahead of the pupils his own age. The difficulty in pronouncing his last name was settled by schoolmates; they called him “Trotsky.”

It was different with my little daughter, aged six. Her early childhood was spent in the Ukraine under abnormal conditions. She lived there in isolation without any playmates. She was at times kept in the house for fear that some of the hooligans who invaded the town off and on might injure or even kidnap her, which was not a rare incident. She spent all the time with her mother to whom she clung with great tenacity. The school, full of boisterous children who talked in an alien language, was abhorrent to her. The first day she was taken back home in tears and refused to go to school. For a few days, I went with her and waited for her until class was dismissed. However, being a bright child, she picked up the language quickly. She became one of the mob and the loveling (sic) of the teachers. She never gave us any trouble since that time.

My son began to take piano lessons in Russia in early childhood. He made good progress, and his teacher--a woman prominent in this field--was enthusiastic and confident that he would be successful. My wife was very keen about his music, and the fact that there was no opportunity for him to continue his lessons greatly upset her. The state of her mind became alarming, and it was clear to me that unless I became independent I was heading toward a catastrophe. Independence meant money, and this I could obtain only by practicing my profession. For this I needed a license, which could be gotten only through examination. This could not be done before late Spring of 1923, and it was then July, 1922. It was inconceivable that I would live, up to that time, on the bounty of my relatives. None of them was rich, and some of them had a hard struggle to make ends meet.

In desperation, I went to see an influential doctor named Boyer who was on the Board of Medical Examiners. He was kind and understanding. He told me to practice medicine unofficially until I got my license. I was relieved and grateful. The examination loomed formidably. I had graduated from medical school 12 years earlier, and in such a length of time one is apt to forget the theoretical part of the medical curriculum, such as anatomy, pathology, and other adjuvant subjects. My English was by no means sufficient to take a written examination. It was hard to study because of lack of privacy and generally unfavorable conditions. However, I had won the first round, and the prospects brightened.

At once, I became active. I found an inexpensive two-room office, and with a little money provided by the family I got some primitive equipment and the most necessary instruments, some of them second-hand. I put up a shingle and waited. At first, my practice was limited to people of Jewish and Slavic extraction. Little by little, American-born people began to come, most of them of the laboring class.

My English was bookish, and the language of the street with its slang was entirely alien to me. This resulted in tragicomic incidents in and out of the office. Once I was descending in the elevator from Harry's office. It was crowded, and a couple of boys were making a great deal of noise. My vanity took possession of me and, in order to show my “knowledge” of English, I turned to the boys saying, “Please be silent.” The boys were not impressed; the people in the elevator looked at me in surprise; and Harry, instead of making a joke of it, remarked sternly, “This is a proper expression in the pulpit but not in an elevator.” I was then fully three days in the country. When I related the episode at my sister's house, her boy, aged 10, exclaimed, “What do you mean, ‘Be silent?’ The word is 'Shut up!’” -which sounded like “Sharap!”

A patient of mine who had been coming for treatments for some time told me once that he was leaving town because he was “fired.” Seeing my embarrassment at not understanding, he corrected himself with, “I was canned,” which stumped me altogether. All I knew was that I was losing a patient for some inexplicable reason. Another time when I asked a patient how his appetite was, he said, “I eat like a bull moose.” I cut short my interrogation.

These were incidents of no consequence, but something happened to me while attending a patient in the hospital that cast a shadow over my practice. It created an inferiority complex of which I never rid myself completely. The patient was a Jewish woman. Her main complaint was pressure on the abdomen, and she was constipated. The nurse in attendance asked me if it was permissible to give her an enema. The meaning of this word escaped me, and I was hesitant for fear of making the wrong decision. Her husband, who was present, guessed the difficulty and whispered to me in Yiddish the meaning of the word. (I was at that time one month in practice.) Later, he remarked, “I understand you were a successful doctor in the old country; you should have stayed there.” As if I did not know it! I decided to limit my practice for the time being to office visits.

When my practice progressed sufficiently, I rented a little house and bought some furniture on the installment plan. Later, I got a second-hand piano, and my son began taking lessons again to the great satisfaction of my wife. We now had privacy, and the tensions relaxed. I also had a chance to study for my State Board medical examinations undisturbed although, strictly speaking, my real studying was limited to one month prior to the examination scheduled for May of 1923. In April, I went to Minneapolis, and Dr. Weber (another foreign doctor) joined me. There, in a little stuffy room in the heat of a premature summer, we studied for 18 hours daily, and I passed the examination satisfactorily. I was now a full-fledged doctor, and I had time to look around and get my bearings on my new life. I liked this free country, and I found the people friendly and helpful. It was not their fault that I could not adjust myself fully to the life here.