Chapter: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

A Russian Chronicle

The Tale of Michael L. Zlatovsky

Chapter 16

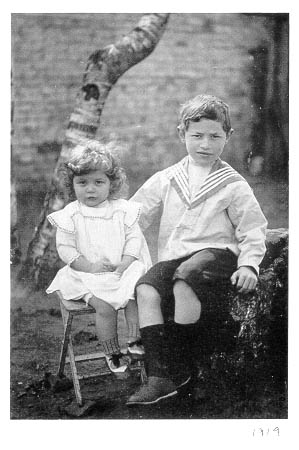

My daugher Helen and son George, 1919

The Socialists of all shades at that time recognized the supreme authority of Marx and Engels and their theory of economic determination. That theory is that the form of government and mode of life in all aspects of society are determined by the economic factors under which the society lives at any given historical period. In accordance with this theory, a social revolution may become successful only in a highly industrialized country. In such a country, the means of production and the capital are concentrated in the hands of a few. The mass of the people become proletariat slaves of the machine. The workers revolt, having nothing to lose but their “chains.” They seize power; they expropriate the exploiters and take matters into their own hands. They then establish a Communistic state, which is governed by the following principle: “From everyone according to his ability, to everyone in accordance with his needs.” No coercion is contemplated.

Lenin, the erudite Marxist, a realist of infallible logic, realized the impossibility of establishing a true Communistic state in a land ruined by civil war, whose economy was based mainly on agriculture, and with a negligible industry. He demanded a halt, at least temporarily, to Communistic experiments. The year was 1921. His arguments were all the more convincing because in the winter of this year occurred the revolt of the Kronstadt sailors who were the avant-garde of the revolution. They demanded free trade and relaxation of other restrictions that had been imposed on the people. The revolt was suppressed, but Lenin called it a memento mori for the regime. His will prevailed and a new economic policy known as the “NEP” was instituted, of which more later.

The “NEP” was a breathing spell after all the hardship, hunger, and ruin the country experienced during the period of so-called “war-communism,” the years 1917-1921. How did people live during those fateful years? I myself was better off than most of the common people but by describing my own trials and tribulations one gets an idea of the general situation at that time.

Like most of the members of the bourgeoisie, I was financially ruined. My practice deteriorated; the money I had accumulated was worthless. I invested 5,000 rubles in liberty bonds under the Kerensky regime, and they were valueless. One could find them posted on outhouses in the marketplace, just “to spite.” I was forcibly separated from my family. However, I kept my grievances to myself. I never objected to the regime by words or deeds and, therefore, did not expose myself to prosecution. I lived among friendly people and grateful patients who would never denounce me to the authorities as so often happened to entirely innocent people. I also had a protector in the person of Stepan who had great power in the Village.

I was never arrested and was spared house and personal search, which were regularly undertaken at the height of the terror period. Economically, I was also a privileged person. All employed people were divided into four categories and given “rations.” The unemployed had to live, or rather starve, on their own resources. Rations were given in accordance with the importance of the job one did. The first and second categories included workers in the heavy and light industries. Doctors were third-class citizens. I was assigned to a big military hospital which formerly was “Nicolasky” but was now a “Red Hospital.” I was allowed 1-1/4 pound of bread daily. It was certainly enough for a single man.

The trouble was in the system of distribution. Because of disrupted transportation and general neglect, the bread, made of coarse flour mixed with different surrogates, was not given daily but at long-spaced intervals. Thus, I would receive a big stone-like loaf of bread. It had to be cut with an ax and then would be found moldy and unfit for consumption. Beside the bread, we were allowed a bottle of crude linseed oil, which was labeled “fats,” a couple pieces of sugar if there was any, a herring or piece of meat of uncertain origin. This was the weekly ration. It is evident that such rations were insufficient to sustain life for any length of time. Some supplemented it with barter or by black market dealings, which were expensive and risky. The less fortunate died of starvation. I, as a doctor, observed dozens of my patients in the village dying of no other cause but lack of nourishment. Luckily for me, I also obtained a civilian job as a sanitary doctor in the village of which Stepan became commissar. As such, it was my duty to inspect periodically the warehouse where food was kept and distributed, to visit government eating places, and also to watch over the health of the employees in these places.

The commissariat paid with money that was of little value. Replacing the former 20 and 40 “kerenkies” were pieces of paper of which the lowest denomination was 10,000 rubles. It took at least 10 of them to buy a few pieces of sugar on the black market. There was in circulation a great deal of counterfeit money with the brazen notation, “Ours are as good as yours.” It was not the money that was a help to me but the privilege of getting food unofficially from the warehouse due to the management's good will. I was also entitled to a free meal in the communal “restaurants.” With all that, I didn't live in luxury, but at least I did not go too hungry.

Next to food, the matter of most importance was clothing. Wintertime is so cold in Leningrad that in comparison Minnesota and Dakota could be termed as temperate. In this respect, I was also lucky. Not long before the second revolution, I invested--this time wisely--a couple million rubles in a fur coat with a collar so big that it covered not only the back but also the front of the head including the nose. With it also went a pair of fur gloves. The next great help to me was a pair of large solid boots. A tale hangs on these remarkable boots.

When the Whites were at the gates of Leningrad, I was commandeered to the front with a party of first-aid personnel. I was in civilian clothes at that time, and I was outfitted in the hospital in a military uniform. I was given a trench coat which reached my ankles, a cap two sizes too big, and boots which belonged at one time to some giant of a soldier, now dead. It was mid-summer 1919. I cut a ludicrous figure in this outfit and it was hard to walk, my feet being always in the middle of the boots, but little by little I decided not to part with the boots in view of the coming winter. Thus, when I came back from the mission, I surrendered my coat and cap with pleasure, but I retained the boots despite the urging of the chief of staff and the threat to report me to the military.

The boots stood me in good stead in the winter. The hospital was away from the Village. Transportation in the record-cold winter of 1919 was disrupted to the point of being non-existent. To shorten the distance, I used to cross the Neva River, and there on a windy day the cold was at its worst. I would put on two pairs of socks--courtesy of the commissariat--and wrap my feet with a few yards of flannel converted into strips from an old flannel shirt. Then I put on the spacious boots and the fur coat to which a bag was strapped. This was a common usage at that time due to the hope of getting food, somewhere, somehow. This way I would begin my trek to the hospital. With all these precautions I was not too comfortable, but at least I did not freeze my feet as happened to one doctor of our hospital who had the same bright idea of crossing the Neva.

The work in the hospital was not hard, but it was heart breaking and dangerous. The hospital at that time was an assembly point for the soldiers from the front, most of them suffering from the dreaded disease, a highly infectious typhus fever, also known as hunger fever or trench fever. The hospital was badly heated and sometimes not heated at all. There was hardly any medicine, and proper food for patients in this condition was unavailable. Sometimes there was not even water to quench the thirst of the fever. You were helpless in the face of suffering. Some of the doctors got the infection, and three of them actually died of the same disease. If I escaped the infection, it was because I had had this disease in my boyhood and was immune.

On top of all this, the Chief was pale, anti-Semitic to the core, and his attitude toward the Jewish doctors was oppressive. It was some kind of advantage that the family was away under such conditions.

I was lonely and there was the question of cooking, heating, and cleaning. It was dangerous to keep an apartment all to myself lest some undesirable family be put in it. The problem was solved by admitting a Jewish family of three. The man was a decent, meek fellow. The woman was bad-tempered and unscrupulous. She robbed me blind of food and household goods. However, she attended to all house-keeping needs, and she made the rations go far. She would cut the bread, scrape off the mold, crush it into powder and bake it again. It was then somewhat edible. Above all, I was not alone, although at times I wished I had not set eyes on my tenant hostess and her abominable sister--some kind of tart who became more or less a permanent feature, especially at meals.

The winter of 1919 was not only the coldest but also the hungriest. All favorite rations were reduced. The people out of orbit of the regime who had been given a 1/4 pound of bread daily now received some oats in small quantities. Once, riding in the streetcar, a rare occasion at that time, I overheard the following conversation. Said one woman, “If you take the bones of herring and the peelings of potatoes and put them through a grinder, adding a few drops of oil and a little flour, you will get passable pancakes.” “I know,” said the other woman, “but where will I get the flour?” In the wake of hunger came epidemics that depopulated the village and the city at large.

It was at that time that the people took to cutting trees and breaking fences for fuel. Our yard, prior to the revolution, was kept meticulously clean. There were flowerbeds, shrubs, and a few trees. A nice wooden fence with a fancy iron gate protected the yard. On both sides of the gate were two tall posts on which lanterns were mounted. The trees and shrubs went for fuel, but I objected to breaking the fence. One morning on leaving the house, I found that the fence together with the posts was gone. “Serves you right,” said my tenant. “We could have used it as much as others.” With the trees and fences gone, groups were formed with the tacit consent of the commissariat to break up empty houses.

The governing dogma of “from everyone according to his ability” was observed in this case, and since my ability to break up a house was very limited, I was little benefited by this plan. I had to depend on barter. In the village, there was a big eight-story apartment house, now empty. It could not be used completely for fuel, so they did the next best thing; they removed all the wooden parts including the floors, windows, and doors. It was a terrifying sight. The building with its gaping holes looked like a corpse with open eyes.

The only form of clothing issued to the population during this horrible winter was some sort of sweater. It was made of dark cloth stitched at the seams with white thread. As a man in the know explained it, this phenomenon was due to the fact that the women in the factory were stealing the dark thread. Stealing in industrial plants, factories, and offices became such a common occurrence that in intimate circles the question would be asked, “Where do you steal?” No offense was meant. “Steal from whomever you can and lie at all times,” became the guiding principle of the day.

The contrast between the present life under Communism and what it should theoretically have been was brought home to me most forcibly on one occasion. It was a dreary winter day when I came to the communal “restaurant” in my official capacity as a sanitary doctor. The restaurant was housed in a dilapidated, un-heated building. The big kitchen that was also the eating-place was damp and beclouded by the vapor coming from a big boiling kettle in which some potatoes and a few lonely carrots were swimming. Some stale bread was in evidence. The tables were bare. The silverware was a collection of knives and spoons of different sizes, mostly rusty and defective. Forks were conspicuous by their absence.

It was my duty to taste the food before it was served. It was not ready, so I sat down. The day in the hospital was very bad, the long walk was exhausting, and the environment was depressing. The vapor condensed into droplets running from walls and looked to me like shedding tears at the fate which befell us all, and myself in particular. Luckily, on a bench I found a book without a cover and missing its title. From the text, I learned that it was Utopia by Thomas More. At first I read it without great interest, but then I came across a passage that became absorbing. A communal dining room in Utopia was described. There was a magnificent hall, tables covered with expensive, spotless tablecloths, vases with beautiful flowers on the table. Lovely girls, richly dressed with silk sheaths around the waist held by silver buckles, served delicious food and choice wines to the patrons. I was so engrossed in this picture of Utopia that I forgot to taste the food before it was distributed. Silk sheaths and silver buckles indeed! I gulped my soup in a hurry and left in disgust.

It can be seen from this narrative that, although a privileged person, my life nevertheless was hard and, at times, unbearable. The most aggravating aspect was worry about my family. The Ukraine was seething with unrest, civil war, and rapid changes of government. The Germans said they recognized the sovereignty of the Ukraine, but actually it was dominated by the Germans through a puppet ruler, Letman Skoropadsky. With the defeat of Germany, Skoropadsky fled, and the Ukraine became independent under the nationalist, Letman Petlura, who distinguished himself by initiating bloody pogroms against the Jews. In turn, Petlura was expelled by hostile forces. He fled to Paris where he was killed by a vengeful Jewish refugee student. From then on, the Ukraine suffered changes of government 12 times in less than two years until it became a no-man's-land where bands of hooligans roamed the country robbing and killing the Jews.

Exchange of letters stopped, and I had no way to communicate with the family or to send them money to live on. Once I made such an attempt. It was at the time when Denikin was in domination and, since the Whites had a great deal of Tsarist money, it became the accepted currency. Through much trouble and at great risk, I obtained a few thousand rubles of Tsarist money and entrusted it to a friend who was stranded in Leningrad and was trying to make his way back to the Ukraine. The man was arrested by a Bolshevik patrol, and when he reached his goal after having been imprisoned for five months, the regime had changed, and the money was valueless.

Once while in the hospital, I glanced at the paper and found the following item: “One day (the date escapes me), the Green Band (so called because their leader was an escaped convict named Zelena, which means green in English) invaded the town of Belaya Tserkov and killed more than 200 Jews--men, women, and children. Fires were set to the Jewish quarters, and the town is in a shambles.” Under the impact of this bit of news, I collapsed.